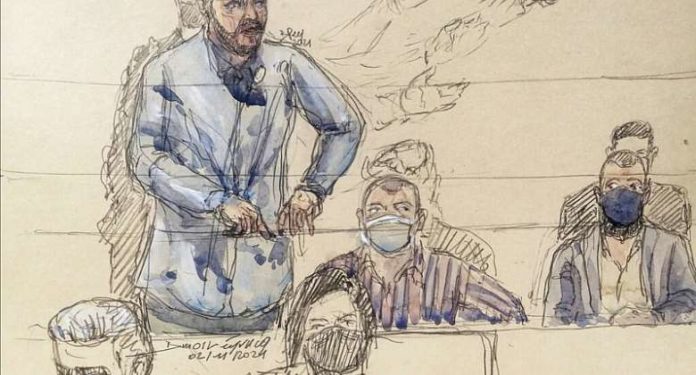

On Tuesday, the Paris attacks trial focused on the case of Mohamed Abrini, one of the passengers in the three-car “convoy of death” which brought the killers to Paris on 12 November 2015. At the last moment, Abrini decided that he could no longer be part of the plan. He returned to Brussels by taxi in the middle of the night.

One moment of silence summed up Tuesday’s six-hour hearing at the special criminal court in central Paris.

Tribunal president Jean-Louis Périès asked the accused Mohamed Abrini why, since he had pulled out of the Paris attacks in November 2015, Abrini allowed himself to be enrolled in the Brussels bombing plan five months later, only to renounce again at the last moment.

“It’s an excellent question, Mr President,” said Abrini after a long pause.

“I hope you have an excellent answer.” Unfortunately, Abrini did not.

Promise to ‘light a lantern’

Earlier this month, describing his involvement in the preparation of the Paris attacks, Mohamed Abrini promised the court that he would “light a lantern” with his revelations this week.

He failed to keep that promise. Abrini’s answers before a crowded tribunal on Tuesday were confused, frequently evasive, contradictory, imprecise, unclear.

“It’s complicated.” the witness repeated throughout his interrogation. That we can believe.

Dressed in an open-neck white shirt, pale under the courtroom television lighting, with deep shadows under his eyes, Abrini looked tired.

He has already admitted that he was “scheduled” by attacks coordinator, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, to be one of the Paris killers. The two men spoke in early September, 2015, in the Belgian city of Charleroi.

Abrini claims that, at the time, he was trying to re-start his life, after five years in prison and a short visit to Syria to see the place where his younger brother, dead fighting in the ranks of Islamic State, had been buried.

“I was working, I was in the middle of preparations for my wedding.”

Abaaoud had other plans.

“He told me I was going to be part of a project . . . But he gave no details. That was his way. I knew nothing about the Bataclan, nothing about attacking France, nothing was clear.

“There was a project, and I was part of it. That was all I knew.

“I didn’t say yes or no. I said nothing. I had a problem of loyalty with Abaaoud. He was a friend for 20 years. He risked his life in Syria to recover my little bother’s body. I didn’t want to get into a confrontation.

“But I knew I couldn’t attack people like that in the street, kill people …” And so the contradictions began. Abrini claims that he knew nothing of the “project”. But he knew enough to be sure it involved shooting people in the street. It’s complicated.

‘Why was I involved? I have no idea’

Despite his deep conviction that he would not take part in the killing, Abrini left Brussels with the others, traveling with the Abdeslam brothers in the first vehicle.

He has no recollection of their discussions during the three-hour drive. He can’t say who used the phone to keep the lead car in contact with the Belgian coordinator. He is not really sure why he was there at all.

“I wish I could give better answers. I was just out of prison. I was lost. Why was I with Brahim, Salah? I have no idea.”

If Abrini is to be believed, his co-accused Salah Abdeslam, the other survivor of the “convoy of death,” was chosen at the last moment to replace Abrini, nominated by Brahim Abdeslam to wear Abrini’ s explosive vest, shoulder his kalashnikov.

‘Abdeslam should be dead in Syria’

Salah Abdeslam should not be in the prisoners’ enclosure at all, according to Abrini. The younger Abdeslam was not “scheduled” to be part of the 13 November attacks.

“He should be in Syria, probably dead, or in jail with Dahmani.”

Ahmed Dahmani is also accused of complicity in the Paris attacks, and is being tried in his absence. He is serving 10 years in a Turkish prison for people-smuggling and the possession of false papers.

“I don’t have all the answers,” Mohamed Abrini told the court late in the afternoon. “You won’t hear the whole story from me.”

Whether from genuine forgetfulness, confusion compounded by six years behind bars, a determination to protect some of his co-accused, or fear of the long arm of Islamic State vengeance, Mohamed Abrini remains a witness who talks a lot but has very little to say.